CONNECT WITH US

John Muir came into the Feather River country to renew an old friendship with Emily Pelton, a friend who had moved out from the Midwest. He spent most of the winter of 1874-5 exploring the Feather River watershed. He arrived in Marysville from Mount Shasta on December 22, then walked thirty miles to Brownsville where Emily lived. They spent Christmas Eve in Strawberry Valley and then Muir went rambling. It was there that he wrote his famous “Windstorm in the Sierra,” in which he climbs a young Douglas-fir and “sways like a bobolink on a reed” while reflecting on the rejuvenating effects of nature. From Ruff Hill outside of Brownsville Muir witnessed the great Marysville flood that he recorded as “The River in Flood,” a cautionary essay against the mistreatment of our rivers and streams. Both pieces can be found in his seminal work The Mountains of California.

Muir also explored the Middle Fork of the Feather that winter, staying at Hartman Bar with a miner named Jack DeLapp. From there, he followed the wild canyon downstream, eventually climbing to the ridge at Mountain Spring House, wandering into the Fall River and South Branch drainages, sketching Feather Falls, writing about Seven Falls in his journal, and noting massive woodwardia ferns and madrones at Milsap Bar.

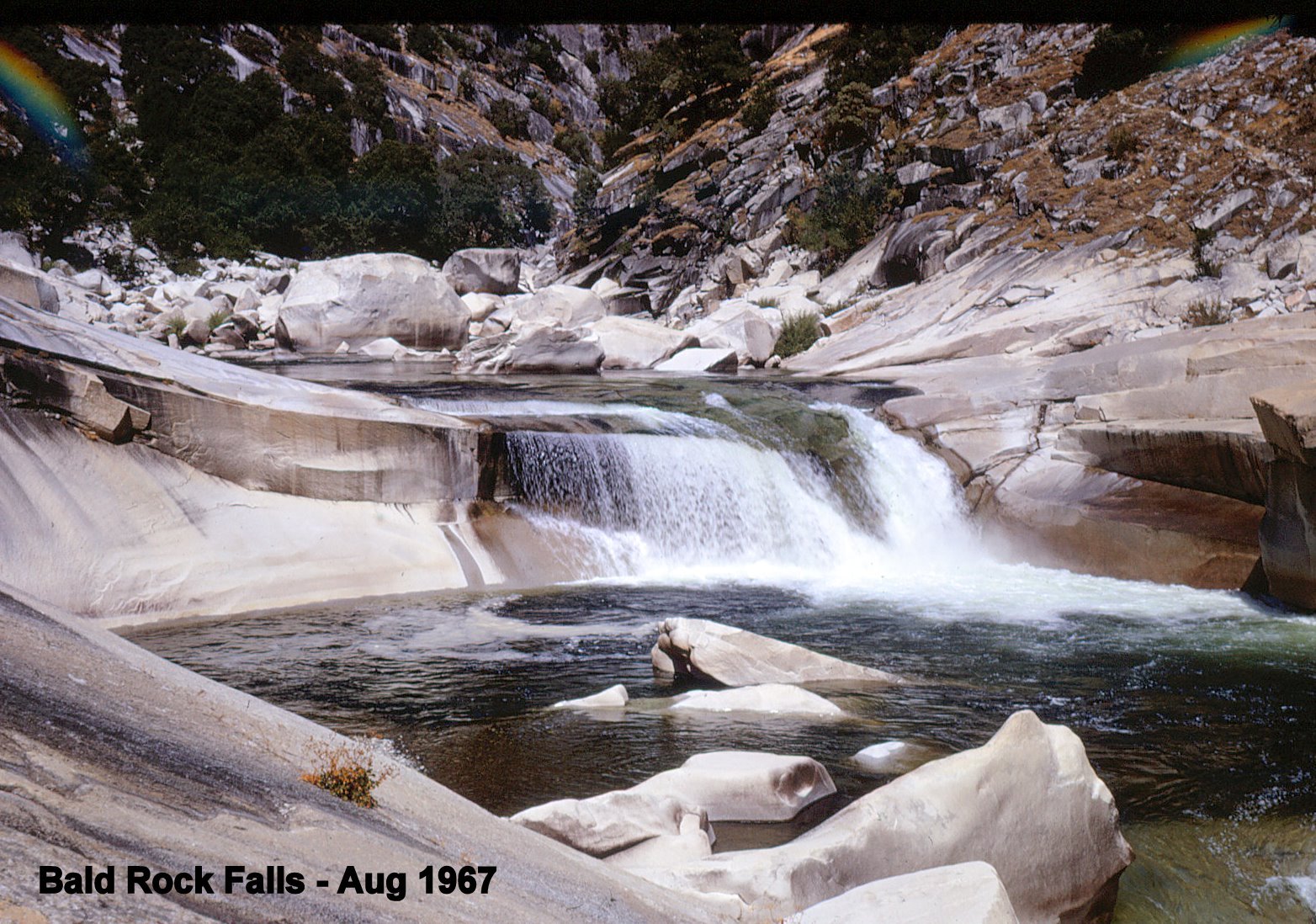

In 2018, while ground-truthing and researching documents related to Muir’s rambles, FoPW board member Will Lombardi found documents from the Department of the Interior related to this part of the drainage. Most compellingly, 50 years after Muir’s rambles, the documents he found mark an early attempt to create a National Park here, which was to have been called Feather Falls and Bald Rock National Park.

Imagine it! An area somewhere in the realm of 40,000 acres set aside for recreationists—A place noted in an initial inquiry as possessing “scenic and recreational value” and “outstanding natural beauty.” Many of us are intimate with these locations, but are unaware of the longer history of environmental protection and collaboration connected to them.

Friends of Plumas Wilderness finds it meaningful and timely to remember that at a moment when John Muir’s Sierra Club was the only organization guarding our public wildlands, it was the Oroville and Allied Communities Chamber of Commerce that, in 1931, was spearheading preservation efforts in this watershed. The Chamber letter suggests, “preserving the natural beauties of its surroundings by conserving the forests and watershed would be one of the greatest assets of the state.” It may seem incongruous now to think of Chambers of Commerce as environmental activists, yet it is hardly far-fetched to imagine why they would be. The country was in the throes of the Great Depression, our wildlands were an egalitarian space, free, open, and available to all, and the watershed above Oroville was and is a special place to explore. The Oroville Chamber saw opportunity in environmental protection. It is this simple: preserve the wild character of a place for people to enjoy and the towns surrounding it benefit in equal measure; destroy it, and your livelihood is gone.

This first attempt at a National Park failed, yet the idea was resurrected by private landholders in the Feather Falls area again in 1946. A woman named Elizabeth Everett, whose niece owned 300 acres near Bald Rock, began the inquiry, signing her letter “Very Forest-Mindedly Yours.” Here too, following World War II, when returning soldiers started families and returned to school, environmental preservation was entrenched in patriotism. It was assumed that the American character was formed by and interwoven with the natural world. Former soldiers returned to fields and streams to reconnect with themselves and their country. Yet the Federal Government suggested Feather Falls, based on their criteria, was better suited as a State Park. The State also passed on formal designation, suggesting instead that it might be best protected as a National Monument due to its natural beauty and Gold Rush history. Finally, the patchwork mix of private, public, and National Forest land made the project of protecting the Feather Falls area untenable in the eyes of State and Federal government officials in spite of vast local support. Still, across the 1946 exchange, in document after document, there is a consistent refrain: “The State Should Preserve Some of the Feather River Canyon. Very Spectacular.”

Like Muir, as we ramble the Feather River Country, members of Friends of Plumas Wilderness see how very important it is to renew old acquaintances. Like the Oroville Chamber we hope to preserve the unique character of this region, and like Elizabeth Everett we are “forest-minded.” These forgotten documents remind us how necessary it has become to remember older collaborations and to rethink our responsibility to the local|wild so intrinsic to who we are as a people. They remind us that our cultural best interests, the best interests of the natural communities of our watershed, and our spiritual and emotional well-being, are also in our economic best interests. These things are not separable. The pandemic has sent people of all kinds in unprecedented numbers back into our wildlands. With increased use comes greater risk. We stand in a unique time and place with a decisive opportunity to reforge connections and increase permanent protections.

Friends of Plumas Wilderness asks that you join us in our efforts to preserve the local|wild. In the last year we’ve become a membership organization. Let’s work together… for our wildlands, for ourselves.