CONNECT WITH US

Things looked grim as the Friends of Plumas Wilderness Board of Directors planned our excursion to the proposed Dixie Mountain Special Interest Area. Sierra Valley was too dry to float and a source told us it was, “Highly likely the driest landscape conditions I have ever seen in April.” California is on track for posting the third driest year since record keeping began. Still, wildflowers are blooming at that end of the county, and it is hard to resist the promise of overnighting in such wonderfully craggy country. Though trouble seems imminent, drought conditions give everyone an early opportunity to explore the higher elevations on foot.

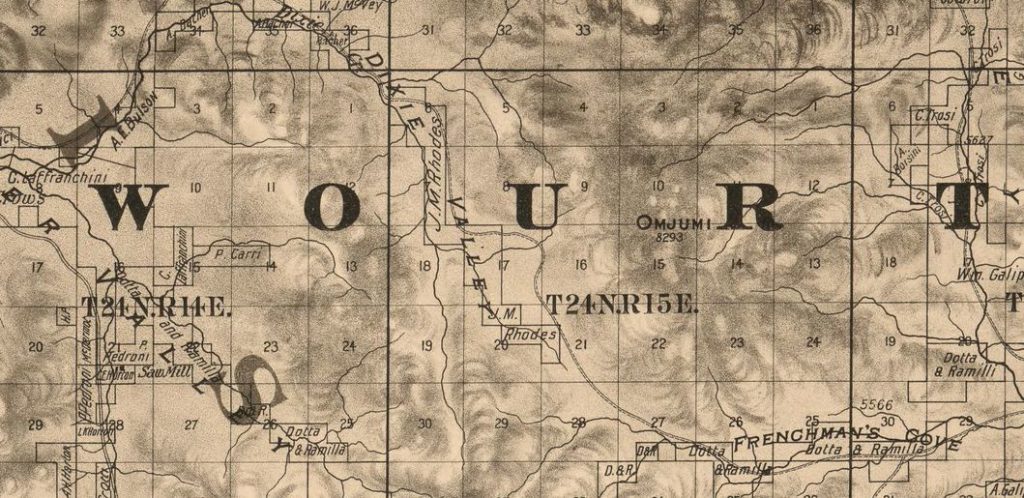

Dixie Mountain (8327’), Dixie Creek, Dixie Valley: Erwin G. Gudde’s absolute classic California Place Names suggests that this name-cluster was “probably applied by Southerners at the time of the Civil War, when Union was a place name favored by Northerners” (110). Arthur Keddie’s 1874 “Map of Plumas County ” seems to corroborate Gudde’s assumption. Bookended by the predominantly Italian Medicis, Guidicis, and LaFfranchinis to the West and Dottas and Ramillas to the East, Keddie’s map shows Dixie Valley claimed by Bulson, Bacher, McVey, and Rhodes, surnames suggestive of a decidedly different origin, making it highly likely that this was a Southern enclave. So too, Loyalton—loyal to the Union—at the opposite end of the valley, seems to verify this notion.

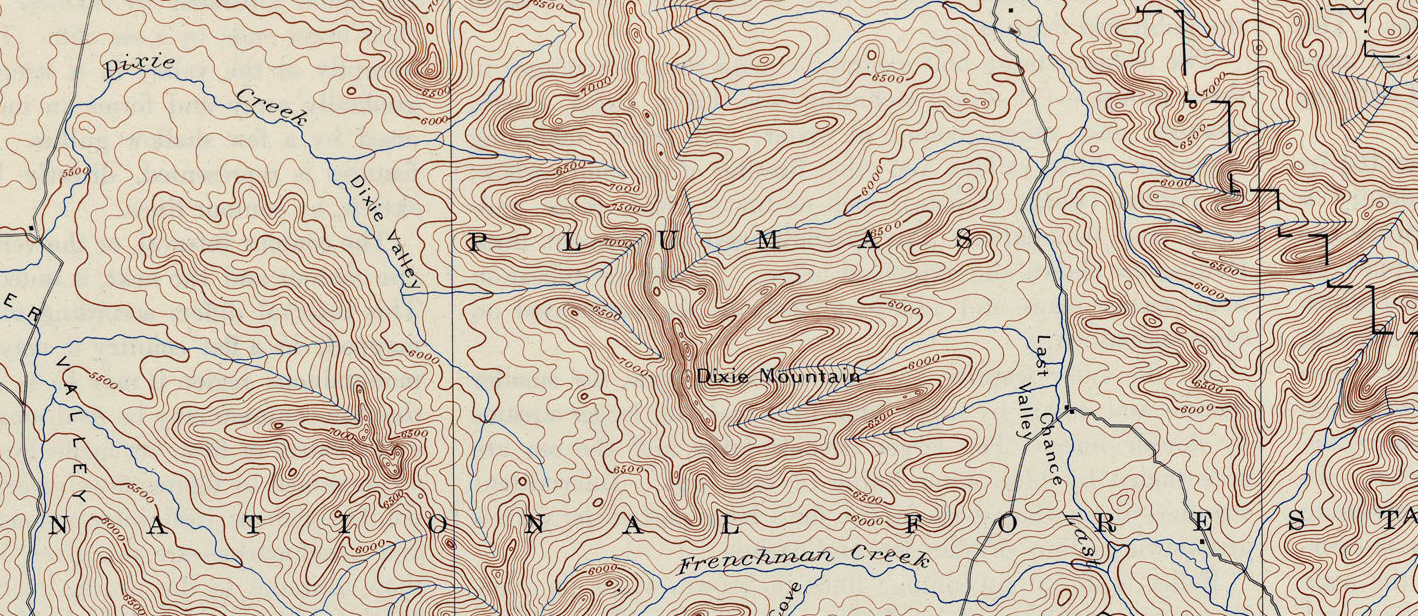

Notably, though, while Keddie’s map names Dixie Valley and Dixie Creek, he calls the peak “Omjumi,” or, what we’ve since learned is related to the Maidu word for “rock.” At the same time, the first topographic map of that region made by the U.S. government, published in 1890, calls it “Dixie Mountain,” and so it remains today in commemoration of the Confederacy. Friends of Plumas Wilderness hopes to restore the Maidu name and to see an Omjumi Special Interest Area established.

Special thanks goes to Dana Galloway and Trina Cunningham for helping us understand the Maidu etymology of “Omjumi,” or, Om jumi in Mountain Maidu language. First, each of them verified that there is no “J” sound in their language, that in this case it would be pronounced as a “Y” or “Ch”; both suggest it is likely the latter. Dana says the “O” would have an accent mark, thus spoken as “Ó” or “Ohm”; “jumi,” she says, would be spoken as “chumí ”; hence, “Óm ChumÍ” or “Ohm ChumME” if we were spelling it phonetically. The meaning of “jumi” is at this time uncertain. Dana indicates it means either “melted” or “urine.” The mountain is composed of agglomerate—melted or formerly molten volcanic flow. Thus, Omjumi may mean, fittingly, “melted rock.” On the other hand, Dana senses it is more likely “Mount Urine.” Trina was sympathetic with this translation. Lying near the headwaters of Last Chance Creek, the main tributary at the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the Feather, this name, too, is tantalizingly provocative of the wild river issuing forth!

The FoPW Board set up camp at Frenchman Lake and set out for a sundown hike that gave us distant views of Omjumi. Gathering beneath an enormous Jeffrey Pine (Pinus Jeffreyi), we found spreading phlox (Phlox diffusa) and red sierra or subalpine onion (allium obtusum) in profusion, as well as a few yellow bells (Fritillaria pudica) among the sage. We spent our night by the campfire thinking about the future of the watershed and our organization’s role in protecting it.

The next morning we drove until we reached the snow, then set out on foot, climbing through beautiful stands of mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius) and perhaps the largest and oldest western junipers (Juniperus Occidentalis) any of us had before encountered. We struck the ridge trail and then found our way among the rocks along the crest, taking in long views in all directions. The view from the lookout is stunning: Lassen, the Lost Sierra, Mount Rose, and distant Nevada peaks. The vast expanse of Red Clover Valley and all of its tributaries unfolded beneath us, contributing to the headwaters of the North Fork of the Feather River. From our prospect up in the wind and sun, among the ancient agglomeration of rocks, we watched cloudshadows play across the landscape below.

According to Forest Service documents, Omjumi Peak, the second highest peak on the Plumas, was initially considered for Special Interest status in the early 1990s for its scenic and geologic significance. The same document noted “high plant diversity,” including some rare species, as well as “potential champion western junipers,” to both of which we can attest. Omjumi rounds out a fascinating case for a diverse assemblage of variously protected lands spanning the upper watershed. It lies between the Adams Peak Inventoried Roadless Area and Horton Ridge, recognized by the State as an Essential Connectivity Area linking Natural Landscape Blocks; northeast lies the proposed Eastern Escarpment Special Interest Area; to the west is the already protected Lake Davis Recreation Area and the Smith Peak State Game Refuge; southward is the Little Last Chance Special Interest Area. As it stands now, Omjumi is recognized as a State Game Refuge. Special Interest status for this incredible mountain would help solidify this region as a prime representative of the Sierra Great Basin Transitional Area. There is a hopeful chiasmus at play in realizing that land protection requires management and land management depends on protection.

Friends of Plumas Wilderness has identified several place names that deserve petitioning for renaming on the Plumas. Recognizing the deep roots of places with Maidu names like Óm ChumÍ is one strategy we hope to employ. Join us as we study, explore, and maintain the integrity of these places, and celebrate their deep history!