FEATHER RIVER CANYONS NATIONAL MONUMENT

OUR SHARED VISION

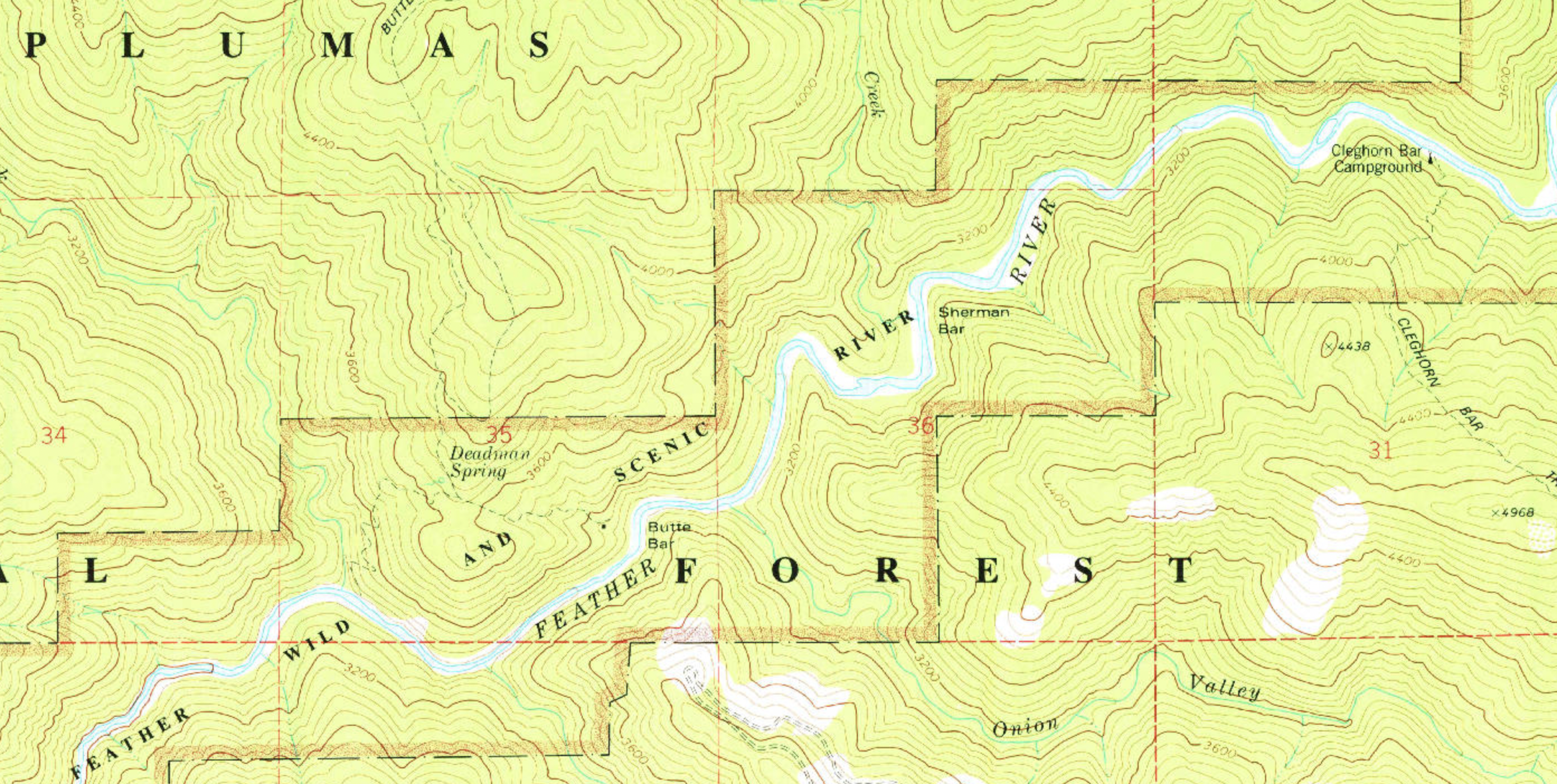

To those who appreciate wild and scenic waters, a trip to the Middle Fork of the Feather River is the equivalent of a painter touring the Louvre or a mountaineer’s pilgrimage to Everest. The river runs longer than a lifespan, and the wellspring of biodiversity crowding its shores holds more mysteries than a single visit can reveal. Sandbars surface from its deep blue pools, and emerald waves lap like a heartbeat over rocky reefs of pebbles and trout. Twisting trails descend under arches of pine boughs waving in a breeze far from roads.

It’s also canvas of memories. In 2005, I visited the Middle Fork and felt the sudden tug of a fish, rod pulsing and the sweet stretch of line as the rainbow made a leap upstream into foam falling from a cataract. In 2018, soft sand cushioned my sleeping bag, and I looked up to see constellations pierce the night as their stars emerged and the lit the world’s dome. It was a place of wonder then, marked by the river’s rugged solitude and the way it carved itself into the land.

In 2020, the Middle Fork burned. Lightning struck: a flame blossomed, smoldered, and merged with canyon winds to become an inferno. For people in Plumas and Butte counties, it was a familiar story: the air itself made visible with smoke as ash powdered windshields; the panic of packing and unpacking and packing again, the trees torching one by one in a wall of fire until the night sky glowed with heat and the crucible devoured miles of forest along with entire towns and left behind only the feeling you had when it was over and houses were gone and pets were missing and people were dead.

I first learned of the Bear Fire while staffing a lookout tower in the northern Rockies. In the mountains of Montana and Idaho there was lightning, but it was smoke haze on the western horizon that troubled me most. As the cloud of ash moved closer, as it cast a shadow over the land and blocked the sun, I knew it meant breathing the cremated remains of a forest I had known since childhood.

Months passed and brought an opportunity to partner with Friends of Plumas Wilderness on a trip to document the Bear Fire burn scar, the first project of its kind on the Middle Fork. It was a dream assignment: with a GoPro, tripod, and backpack, I would visit strategic sites above the canyon rim and stitch together a series of photos illustrating the fire’s aftermath. Autumn had arrived, and in unseen stretches of the forest, embers from the Dixie and Beckwourth Complexes still smoldered.

My journey began south of the river in October of 2021. On the Quincy-LaPorte Road the conifer trees were cloaked in mist that parted just after sunrise to reveal oak stands ablaze with golden leaves. The ground was dry from another year of drought and beams of sunlight slanted across the road as its pavement arced and climbed to higher altitude. Then, rounding the corner, there was a sudden break: hillsides of upturned earth dropped away into drainages, bare under the sky and dotted with rows of stumps. Logging roads crossed the open country. Beyond the stumps more trees stood, black and charred and stripped of branches.

But not all the land was treeless. Crossing the Middle Fork at Red Bridge, I turned up The Hogback, its hairpin curves corkscrewing at steep angles above the canyon’s void. I drove further, and a clearer view of the burn scar emerged. To the north, the fire had torched wedges of forest as its flames pushed or stalled at the whim of winds. Yet unburned acres remained.

The road leveled in Onion Valley, and I looked toward Pilot Peak, home to a long-abandoned lookout tower – the mountain was obscured by clouds, half-hidden in a storm darkening to gray and threatening rain. I pressed on to Fowler Peak in hope of clearer views.

On the PCT near Little Grass Valley Reservoir, a trail marker stands between a two-toned forest. Look closer: a blaze of orange needles covers the floor beneath unending columns of blackened trunks. Rain from the morning left the scorched wood on each snag wet, and steam rose from them as though they had just stopped burning. Wind that once rustled through the canopy now passes unheard without foliage to grasp. Stepping carefully onto stones poking through the soil, testing each one before trusting it with weight, I made my way to the top of Fowler Peak and took in vistas that varied between living and burned.

Why do we mourn when we look upon a fire-seared forest? Do we mourn the animals, the growing trees, the bird chirps and trickle of water? Perhaps we mourn for ourselves and our own idea of the living and the beautiful, the sense of an ending and a feeling that the place we knew will be changed beyond our remaining span of years. Maybe we sense how much life was extinguished in the heat.

Hiking down from Fowler Peak, I felt confusion and loss. Then one wrong step on a mud-slicked rock shot my boot forward into empty air and a quick slip. My elbow crunched against a boulder; a purple bruise bloomed against my skin.

Dizzy and dazed, I stood up and examined the ground. Devoid of vegetation, the soil had smeared into a slippery blue sheet of sludge. Like me, the standing snags had nothing to grip. I thought of the impending rain – a record-setting storm was in the forecast – and wondered about the river. Would runoff trigger mudslides, siltation, and choke the gills of trout I had seen in the Middle Fork? What birds or animals would live here after each tree fell? These questions hung unanswered in the silence, as unreachable as the visible vapor I exhaled in the cold.

More visible was evidence that the Bear Fire continues to mark nature’s reset across a vast region of northern California. This watershed – these burned trees – will flow downstream until they reach almond groves in the San Joaquin Valley, a hospital in Bakersfield, a kitchen tap in Merced. The Middle Fork canyon – more fragile now than at any other time in living memory – remains an artery for the lifeblood of wild and human communities alike.

With new pain in my elbow and doubt in my mind, I continued down the trail as rain began to fall.

– Austin Hagwood