CONNECT WITH US

The Eastside is made magic by the crumbling and eroding hoodoo formations of Lovejoy Basalt, by the broad, lush body of Sierra Valley, and by the peculiar confluence of Sierra Nevada, Cascades, and Great Basin. It’s the site of a natural rewilding that’s been taking place over the last decade, of elk, pronghorn, and wolves returning to the region out of ancient habit. The headwaters is big, open country, and Adams Peak, third highest peak in our watershed and one of five “eighters” on our forest, stands atop its far eastern edge. On the day following winter solstice we set out to climb Adams Peak, the center of an Inventoried Roadless Area that Friends of Plumas Wilderness hopes to protect.

Starting out in the mostly-snow-covered lower forest along Spring Creek, we observed galleries of large black cottonwood (Populus tricocarpa ) and aspen (Populus tremuloides). Climbing the ridge we ascended through Jeffrey pine (Pinus jeffreyi) and white fir (Abies concolor). We observed cat faces on large Jeffrey pines and burned, wolf lichen-covered snags (Letharia vulpina).

Three times we ascended steep slopes punctuated by granite outcrops and separated by relatively flat ridges. At the base of the false summit southwest of Adams Peak were large specimen Jeffrey pine and mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus ledifolius). The winds and terrain made their mark on them: western white pines (Pinus monticola) on the protected rise between the false and true summits grow straight and true, while Jeffrey pines encircling the peak are stunted, their arms wind-swept. One had arms longer than it is tall, all of them swooping leeward from decades of battering.

The north side of the false summit was knee-deep in snow and we post-holed our way upwards. We pushed through ancient mahogany near the top, scrambling among snowy boulders. The mahogany, wreathed in chartreuse wolf lichen, slowed our progress. They grew larger than we knew they could, with multi-stemmed trunks each the size of platters, bark rough and splitting darkly. They created a maze we wound our way through.

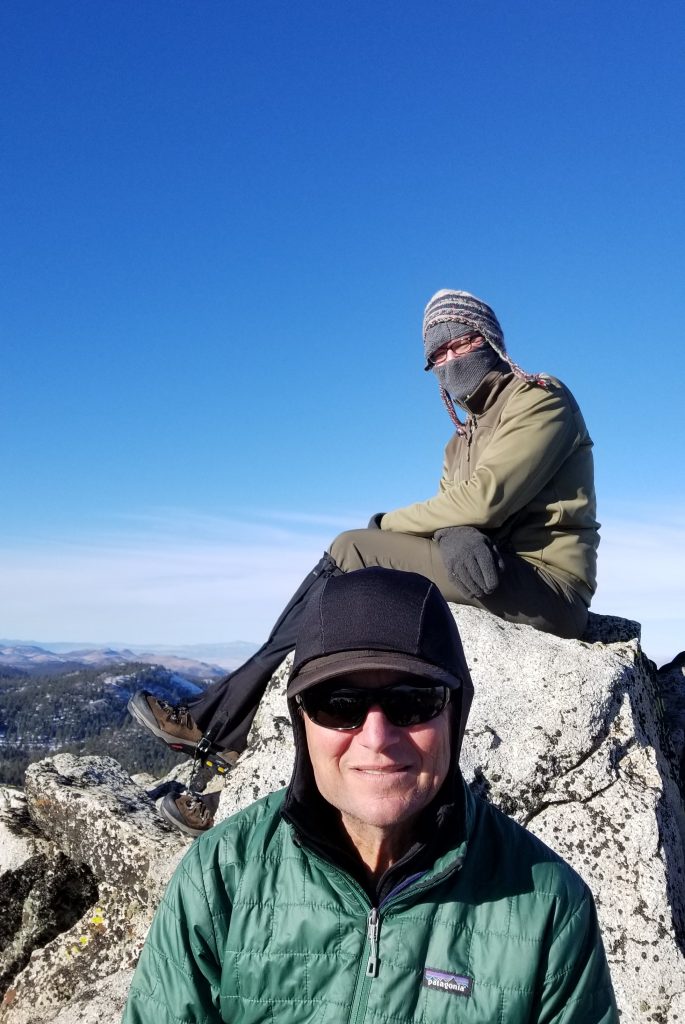

The euphoria of gaining the peak: 360-degree views in the winter light astounded us; from the summit we saw far into Nevada, north to Honey Lake and points beyond, south past Mount Ina Coolbrith, and west into the heart of the Lost Sierra. After a late, hurried lunch, we descended the way we had come. We reached the trucks just after sundown and watched a long, colorful sunset fill Sierra Valley.

Friends of Plumas Wilderness strongly supports protecting the Adams Peak Inventoried Roadless Area and adjacent Forest Service and BLM lands—which meet the definition of Wilderness—from motorized trespass. We suggest the installation of signage indicating the area is non-motorized. Additionally, we have advocated that a portion of the area be closed to motorized oversnow vehicle use year-round. None of the routes that we suggest be closed are shown on the Plumas National Forest Motor Vehicle Use Map. Our proposed improved protections within and around the Adams Peak IRA will conserve the unique biological values found at the southern end of the Diamond Mountains and compliment existing recreation opportunities available on the east side of the Plumas National Forest.

The Adams IRA is surrounded by a sea of roads above Frenchman Reservoir and is located only one hour north of metropolitan Reno. Our winter solstice adventure reinforces that Adams Peak absolutely warrants efforts to enhance and preserve its distinct features, for the sake of sustaining water quality, botanical interest, and community health. Discover it for yourself!